Many Zimbabweans have posted on social media saying “The Zimbabwean dream is to leave Zimbabwe,” as life becomes increasingly difficult.

Noel Ngwenya, aged 44 and from Chivi, Masvingo, spends his days in downtown Bulawayo, the second-largest city in Zimbabwe. Using a loudhailer, he advertises his business of collecting torn or soiled foreign currency notes that have been rejected by supermarkets and other traders. This mostly includes US dollars or South African rand, both of which are legal tender in Zimbabwe. Ngwenya pays his clients 50% of the value of the note they bring, such as US$1 for a torn US$2 note or 100 rands for a torn 200 rand note. According to Ngwenya, selling on the streets is the easiest way to survive in Zimbabwe, but one needs to be creative. He told BBC:

Things are worse after COVID-19, it’s like everyone is now on the road selling something since there is almost no formal employment in the industries.

Zimbabwe’s inflation rate has been gradually decreasing since reaching a high of 285% in August 2022. However, as of March 2023, it was still at 87.6%, leading Zimbabweans to find creative ways to survive.

According to a recent report by the International Labour Organisation, 76% of employment in Zimbabwe is now in the informal sector, where goods or services are sold without registering with authorities. Due to high bank charges and a lack of trust in the banking sector, Zimbabweans prefer to deal in cash or mobile money.

Ngwenya describes himself as an agent for middlemen who have contacts in the US, South Africa, or local banks to exchange torn or soiled cash for good notes. He supplements his unpredictable trade by selling fruit and roasted maize on the side, stating that business is slow these days, and he has to make do with whatever notes he gets, from US$1 to US$100.

Decades of corruption and economic woes have led to the deterioration of the national and inner-city road infrastructure. This presents an opportunity for Mayibongwe Khumalo, 25, from Cowdray Park, a sprawling suburb about 25km west of Bulawayo. He is one of many people who patch up potholes around the city in return for small change from grateful or sympathetic motorists. Khumalo explains:

We fill up potholes because we see them inconveniencing drivers. I’m broke and I wish I could get money, but I don’t want to beg like a blind man.

We have so many blind people in Bulawayo that motorists are no longer touched by their plight. I am an able-bodied person and no one is going to throw money at me. I believe by fixing the roads, those who see value in what I’m doing will give me something. On a good day, like today, I’ve made US$9 and 100 rand and hundreds of Zimbabwe dollars.

Khumalo said he won’t return home empty-handed and can support his wife and three children. He has worked as a minibus driver and tout and occasionally performs as a backing dancer for a popular musician who performs tjibilika music, which addresses social issues.

Sukoluhle Christine Malima, aged 36, operates a restaurant in an old caravan trailer located at a public transport terminus in Bulawayo. She finds it difficult to save enough money to register her business, resulting in her having to pay US$4 fines frequently. She said:

My plan is to raise money for my trading licence, but the constant arrests and increased competition have made things harder. Each time you set aside some cash, the police come to check for licences and you have to pay the inevitable fine.I buy a broiler chicken for US$6 and cut into 12 pieces, which produce 12 plates of Sadza and chicken, giving me US$12 per day.

From there I deduct US$1 for mealie meal, US$1.50 for cooking oil and another US$1.50 for tomatoes and onions, so my profit is around US$2 or US$1.50 per day, which I try and save for my licence. But then the police come again and I am back to square one.

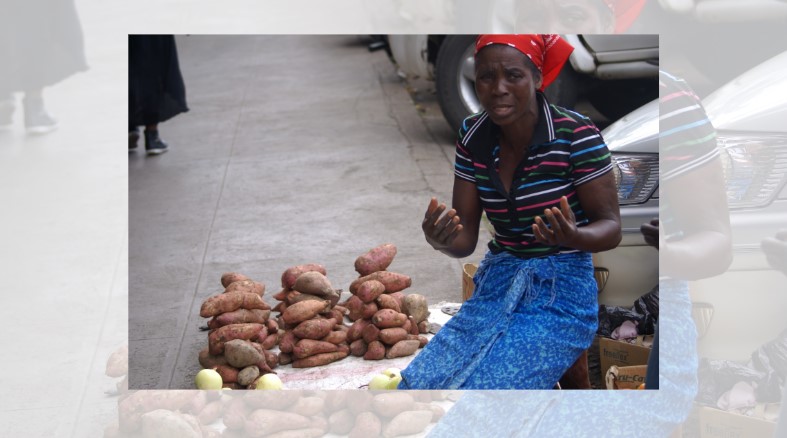

Around 65% of the estimated 5.2 million traders in Zimbabwe’s informal economy are women. The government aims to formalize this sector to increase tax revenues, but they are cracking down on small businesses by sending law enforcement officers to inspect trading licenses and fine those who are non-compliant.

Back to top